G100UL Oshkosh Seminar 2025

GAMI's George Braly gives a presentation on the state of G100UL deployment at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2025. This annotated video includes the presentation and subsequent Q&A section.

On 19 June 2024, Cirrus officially released Service Advisory SA24-14 relating to the transition to unleaded fuels in SR series aircraft. In that Service Advisory, Cirrus suggested the possibility of some “inconclusive” areas of concern regarding GAMI’s G100UL High Octane Aviation Avgas, specifically material compatibility.

On Saturday, November 2, 2024, G100UL Avgas was first deployed to the Reid Hillview airport (KRHV) in California. That day, a number of Cirrus aircraft were fueled with G100UL Avgas. At 6pm MST, GAMI’s head of engineering sent a photograph of three (of five or more) Cirrus aircraft that were refueled with G100UL Avgas that afternoon, to Cirrus CEO Pat Waddick.

The following Tuesday, November 5th, Cirrus amended its June Service Advisory (SA24-14) and released SA24-14R1.

The amended SA24 contains more specific claims about the use of G100UL Avgas than did the original. The “coincidence” in the timing of the release of the revised SA24, following only one business day after the deployment of G100UL Avgas at KRHV and the notice to Cirrus CEO Pat Waddick, is noted.

What was Cirrus alluding to by the words “material compatibility” remains “inconclusive” in the original SA24-14?

In the revised SA24-14R1, Cirrus now states:

While some aspects of the initial Cirrus testing of the GAMI G100UL fuel are encouraging, Cirrus has identified specific concerns regarding material compatibility.

While Cirrus claims their lab testing was done in coordination with the FAA that was not the case as of the date of the meeting with the FAA and GAMI, held on February 29th, at GAMI in Ada, Ok.

Up to that point, (February 29th, 2024), all of the Cirrus testing had been done in secret without any coordination with GAMI or with the FAA.

The specific (and only) material compatibility issue, to which Cirrus refers, arises from what is, most likely, a Cirrus manufacturing process failure during the production SR22T N72DF, or possibly the earlier exposure of that fuel tank to one of the known PAFI fuels which were determined to destroy fuel tanks.

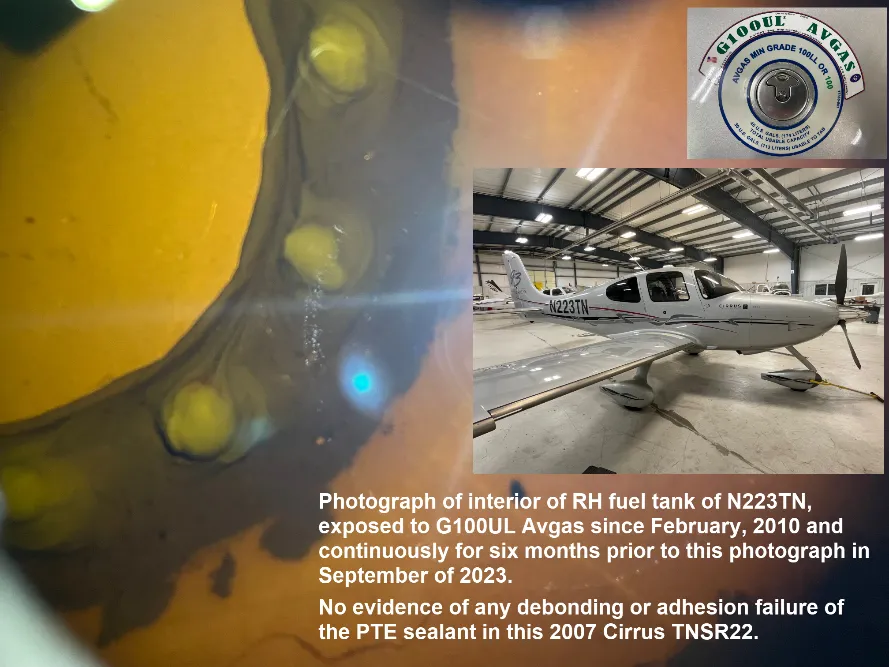

This Cirrus SR22 has had G100UL unleaded avgas in the right hand wing for 14 years.

It is critical to note that the primary “sealant” (which is structural) for the Cirrus fiberglass/epoxy wing is accomplished through the use of the epoxy adhesive used to structurally join or “mate” the top half of the wing shell to the bottom half, during production line assembly. That primary epoxy structural bonding adhesive is not, in any way, implicated, by any of the information stated or otherwise “alluded to” in Cirrus SA24-14 or SA24-14R1.

Cirrus Design, independent of GAMI, fully tested, evaluated, and approved their wing construction for material compatibility and wrote a formal report in November 22, 2013, and provided that report to the FAA.

That report is now formally “FAA Approved” and completely validates the suitability of the Cirrus fiberglass epoxy wings for use of G100UL Avgas.

For reference, that report is Cirrus Design Corporation “G100UL Unleaded Fuel Compatibility with Epoxy Prepregs and Adhesives” Doc. No. 235581.

The “material compatibility” issue to which Cirrus is referring involves a rarely used polythioether (PTE) aerospace sealant which is secondarily applied by Cirrus through the small bottom access covers of the three fuel bays in the left side and the right side of each wing. Note: Cirrus may be the only aircraft manufacturer that uses that PTE sealant for a fuel tank sealant. For the last 75 years or more, the “gold standard” has been the use of polysulfide (PSD) sealants.

Prior to the mating of the upper/lower wing shells, the upper half of the wing has the ribs and spars installed and bonded to the shells with epoxy. After that epoxy bonding is cured, then PTE sealant is applied to the upper half shell and the ribs and spars.

Only after the mating and epoxy bonding of the upper & lower halves of the wing is complete, is there sealant applied to the mating surfaces between the lower portion of the ribs and spars, via very limited access through the small removable panels in the floor of each of the three wing fuel bays on each side of the wing.

That sealant’s only apparent purpose is to function as a “belt and suspenders” to secondarily minimize any contact between the epoxy adhesive and the fuel in the tank, or to protected against inadvertent “leaks” from lack of the complete application of the epoxy to join the ribs, spars and the top and bottom halves of the two wing shells.

The only “material compatibility” “issue” observed and documented by Cirrus was in the lower portion (the floor) of a single wing fuel tank bay - on one aircraft, a Cirrus Company retained “R&D” SR22T aircraft, N72DF.

First: None of the PTE sealant in the wing serves any structural function.

In that connection, it is important to know that the same PTE sealant applied to the interior of the same fuel tank bay, and covering the upper four-fifths of the seams of the interior front and rear spars and the ribs, and also exposed to G100UL avgas for the same duration as the sealant applied to the floor of the same fuel bay - is in perfect condition, with no evidence of any debonding!

However, that sealant application is always applied earlier in the production process, using a “caulking gun” and when there is open and free access to the top “half-shell” of the wing.

The secondary PTE sealant (that partially “debonded”) was applied (blindly, by workmen using a gloved hand) as a subsequent process, applied to the floor of the fuel bay, via small, removable, access panels located on the bottom of each of the three fuel bays on each side of the Cirrus wing.

Second: Visually, the sealant that debonded in the one fuel bay of the single aircraft wing in company R&D aircraft N72DF appears to have been “applied” in a haphazard way and on surface areas grossly outside of the normal areas to which sealant is or should be applied. Visually, from inspection of the interior of that wing fuel bay, it is clear to any pilot or mechanic that the quality of the “workmanship” associated with the debonded sealant in the wing of N72DF was “poor”, and more properly characterized as “sloppy.”

GAMI was first informed of the sealant debonding in the wing of N72DF in late March or early April of 2023, after the conclusion of the highly successful Cirrus flight testing (back-to-back comparison to 100LL) using a calibrated torque-hub to measure torque and horsepower.

Note: The written report of that flight testing completed by Cirrus test pilot Terry LeSage, and provided to GAMI was not merely “encouraging” - the results of that testing, as reported by Cirrus, constitute a statement that the use of G100UL Avgas in the Cirrus TSIO-550K engine provided the same horsepower on lower fuel flows and cooler CHTs as compared to the use of 100LL. Note: Cirrus has objected to GAMI releasing that highly favorable data to the public.

Why? Why would Cirrus object to the public disclosure of that highly favorable flight test data?

Within hours of first learning of that sealant problem at Cirrus, GAMI used a borescope to inspect the fuel tanks of our company owned TN SR22 Cirrus, N223TN. As reflected in the picture, above, that aircraft has had G100UL avgas in its wing for most of the last 14 years, and, continuously, for the last 19 months. None of the sealant in that wing exhibits the slightest hint of any adhesion failure or “debonding.”

GAMI’s initial conclusion, based on that compelling evidence, was that the cause of the debonding in the wing of Cirrus Company R&D aircraft (N72DF) was almost certainly due to a deviation or violation of the required manufacturing process quality control at Cirrus. There are multiple known “process requirements” associated with the application of PTE and other sealants that have to be strictly avoided. Otherwise, sealant will debond in exactly the same way as did the sealant in the wing of N72DF.

Cirrus was quick to tell GAMI that the condition of GAMI’s model year 2007 airplane, N223TN, was irrelevant because prior to 2010 Cirrus used the industry standard sealant, identified as polysulfide (PSD) sealant. Therefore, the sealant in the wing of N223TN was initially (as claimed by Cirrus) thought to be a different sealant than the PTE sealant used in N72DF.

Ten months later, on February 29th, 2024, it was accidentally disclosed by a Cirrus engineer, that Cirrus did, in fact, begin to use some of the same PTE sealant as early as 2006, the year before GAMI’s aircraft was manufactured in 2007.

Immediately, thereafter, on March 4th, GAMI removed a piece of sealant from the fuel tank of N223TN and had it tested by Fourier Transform Infra-Red (FTIR) spectrometry and determined that the sealant in N223TN, exposed to G100UL avgas for 13 years - was in fact the same polythioether (PTE) sealant type as the debonded sealant in the wing of N72DF, which was exposed to G100UL avgas for 3 months.

IMPORTANT:

Cirrus has admitted that Cirrus failed to inspect the wing of the 10 year old N72DF prior to beginning the use of G100UL Avgas! Therefore, Cirrus does not know and cannot assert that the sealant in that wing had not previously debonded due to manufacturing defect or due to other experimental activities for which that aircraft was used by Cirrus; and,

Cirrus did use an SR22T company R&D aircraft to conduct fuel testing with other PAFI fuels, in the 2016 2018 time frame. One of those PAFI fuels was a Shell Oil Company fuel formulation that was rejected by the PAFI program because it destroyed fuel tanks and fuel bladders.

With the addition of the compelling data from GAMI’s Cirrus SR22 wing with PTE sealant after exposure to G100UL Avgas for 13+ years - then in March of 2024, GAMI determined that the most likely cause of the sealant that debonded in the fuel bay of the Cirrus company aircraft was due to, either:

An isolated breakdown in the Cirrus manufacturing process control, which resulted in that limited area of sealant having been “installed” by Cirrus in the bottom of that wing, in a manner contrary to the requirements of the manufacturer of the sealant (PPG Aerospace Sealants); or,

Due to the earlier use of that same Cirrus Company R&D airframe (N72DF) for other experimental fuel testing conducted by Cirrus for other candidate fuel developers.

Cirrus has not offered any other explanation that is consistent with the known data.

So far as GAMI can determine, from inspecting the photographs of the sealant that partially debonded at Cirrus, at no time was any of the associated epoxy bonded joints & seams exposed to fuel, in any way, as result of any peripheral debonding of the excess PTE sealant.

There is no evidence that any portion of the sealant that debonded was “liberated” to be able to migrate around in the fuel tanks. Note, the sealant has a specific gravity higher than the fuel, and therefore always sinks to the floor of the fuel tank, making it difficult to migrate through the ribs separating the fuel bays.

IMPORTANT: The secondary (PTE) sealant debonding in the isolated fuel bay of the wing of the single Cirrus aircraft, and if later observed in other aircraft in the fleet, would, in no way affect the ability of the fuel tank to seal or (due to the favorable design of the Cirrus fuel pickup screens in the fuel tank) would any such debonding create any possible risk for obstruction of the normal flow of fuel to the engine.

For those reasons, there is no safety of flight issue.

The FAA fully participated in the sealant investigation and has reviewed all of the same data that Cirrus has reviewed.

The FAA has advised GAMI that, based on that investigation, there is no “safety of flight” issue with the use of G100UL Avgas in any Cirrus aircraft.

Cirrus was able to document only one (1) instance of partial debonding of a particular type of secondary fuel tank sealant (PTE).

Cirrus does not know if that sealant had debonded before the beginning of the use of G100UL avgas, and the debonding was only later discovered, by accident.

Subsequent exhaustive “soak” testing of six (6) different Cirrus SR22 fuel bays, all with the same type of PTE sealant, established that there was no adhesion failure / debonding for PTE sealant applied (by Cirrus) to any of those six, discrete, fuel bays. Some of that soak testing lasted for two to four times as long as the previous use of G100UL in the wing of N72DF had lasted.

GAMI’s 2007 model TN SR22 right hand fuel tank has, for the last 14 years been routinely exposed to G100UL Avgas. Further, for the last 19 months, that wing fuel tank has been continuously exposed to G100UL Avgas. Borescope inspection of the interior of the fuel tank establishes that the sealant, as applied seventeen years ago, is still in original pristine condition. There is no hint of any de-bonding, anywhere in that fuel tank.

That aircraft is flown regularly and G100UL avgas is normally kept in the RH wing tank, continuously. That aircraft has had various successive production batches of G100UL avgas in the wings since February of 2010 and has G100UL avgas and only G100UL Avgas in that fuel tank, continuously for past 17 months.

Immediately after Cirrus disclosed the single incidence of fuel tank adhesion failure, in late March of 2023, GAMI began an intensive and exhaustive investigation to determine the root cause of the failure of the PTE sealant in the isolated wing at Cirrus.

That investigation has been overseen by a senior FAA propulsion Project Manager, and others in the FAA. At no time has GAMI been able to replicate any debonding or adhesion failure in any of the six different fuel bays from two different Cirrus SR22 wings, nor in the wing of N223TN, GAMI’s 2007 TN SR22 Cirrus;

The only PTE sealant that GAMI has ever been able to force to debond in a repeatable manner and consistent with that debonding observed at Cirrus, were individual 1” x 5” x 1/8th thick test “coupons” of sealant applied to Cirrus fuel tank substrate - and the only ones of those that have consistently debonded were those “coupons” that were purposely applied, with improper, incomplete, or inadequate “surface preparation” or application of the sealant after its working life (30 minutes) had expired, or otherwise in violation of the written package insert instructions, as required by PPG Aerospace;

On February 29th, 2024, Cirrus CEO Pat Waddick and two Cirrus engineers made a trip to GAMI’s facility, in Ada, Oklahoma. There were three senior FAA engineers on site for that comprehensive review of all of the results of the investigation completed by GAMI and by Cirrus. Other Cirrus employees from Duluth and from the FAA also participated;

During that inspection trip, the Cirrus manager and engineers and the FAA personally inspected the referenced portions of the six additional fuel bays, from SR22 Aircraft and personally verified that there was no evidence of any sealant adhesion failure;

They also inspected (visually and by borescope,) the interior of the RH wing of N223TN, the GAMI company owned Cirrus, with PTE sealant, and verified there is no sealant debonding in that wing.

The type of sealant at issue, known as polythioether (PTE), is rarely used in general aviation. In fact, Cirrus is likely the only OEM known to have used that particular type of sealant in fuel tanks. The most common type of sealant used in general aviation fuel tanks is polysulfide sealant (PSD). There is not a single example known anywhere of any failure of PSD sealant when exposed to G100UL Avgas;

The product manager for PPG Aerospace Sealants, Mr. Bill Keller, has reviewed relevant portions of the data related to the sealant failure at Cirrus. Mr. Keller has made the observation that the data is consistent with a failure to properly prepare the surface, or some other non-compliance with the package instructions.

According to Cirrus engineers, Cirrus used PSD sealant for many years, before intermittently switching back and forth between PTE and PSD between 2006 and 2010. From approximately 2010 through March of 2023, Cirrus used only PTE for their factory applied sealant.

IMPORTANT: Immediately after the discovery of the PTE debonding in the floor of one wing at Cirrus, Cirrus advised GAMI that Cirrus had changed back to using only PSD sealant on their production line. Why did Cirrus feel compelled to immediately, without further investigation, change, and began using (again) the historic industry standard sealant?

From February of 2023 through July of 2023, Cirrus conducted a series of laboratory “coupon” tests of PTE sealant. According to the report submitted to the FAA in early August of 2023, a few of the dozen coupons soaked in mixtures of both 100LL and G100UL Avgas, exhibited small portions of the edge or corner that were consistent with minor debonding. None of that “debonding” resembled anything similar to the debonding in the wing tank of N72DF.

However, for inexplicable reasons, that report (submitted to the FAA in August of 2023) failed to include the most significant data!

During the subsequent February 29, 2024 meeting at GAMI, with Cirrus, with the FAA present in person, it was (apparently only by inadvertence) revealed by a Cirrus engineer that, in fact, Cirrus had also done “coupon testing” on a number of identical PTE sealant coupons that were soaked at elevated temperature in pure, conforming, G100UL Avgas, and none of those coupons exhibited any indication of debonding or adhesion failure. In addition, Cirrus had also soaked PTE sealant coupons in pure 100LL, and they exhibited no indication of any debonding or adhesion failure.

Observation 1: In the world of scientific / engineering peer reviewed publications, any discovery that an author of such a publication failed to reference or include known data created by the author that is directly contrary to the portion of the data that was relied upon in the journal article, would normally cause the journal article to immediately be withdrawn.

In addition, the author or authors will normally face harsh criticism from their peers, or be banned from further publication in the relevant journals.

Observation 2: Title 14 CFR § 21.2 (Falsification of applications, reports, or records by the holder of an FAA Type Certificate) is grounds for the FAA to suspend or revoke any type certificate issued under Part 21 of the Federal Aviation Regulations.

Cirrus reports that it has conducted testing of many or all of the previous PAFI candidate fuels. As described earlier, some of those PAFI candidate fuel chemistries were known to destroy wing fuel bladders and/or to “strip the paint” from the wings of aircraft. GAMI has received no documentation from Cirrus that would demonstrate that N72DF (an airframe specifically retained by Cirrus for company R & D) was not used for the earlier PAFI fuel testing.

IMPORTANT: The following fact cannot be emphasized sufficiently: Before fueling their 2014 company SR22T (N72DF) aircraft with G100UL avgas in late January of 2023, Cirrus failed to inspect the fuel tank of the wing in which Cirrus later observed PTE adhesion failure. For that reason, it is not known if the later observed sealant failure in that fuel bay occurred prior to the use of G100UL Avgas, or not.

Conclusion related to “material compatibility”: Given all of the undisputed sealant data (showing no debonding of PTE sealant in Cirrus fuel tanks) and the opinion of PPG Aerospace, the manufacturer of the PTE type sealant, the most likely cause or causes of the PTE sealant adhesion failure at Cirrus were:

Below is a You Tube link to a 23 minute YouTube video.

In this video document, you will see the lower floor of the inboard fuel bay of a Cirrus wing, with 10+year old PTE sealant, which has been exposed to G100UL Avgas for months, and at elevated temperature for most of that period.

GAMI considers the data presented in the following YouTube Video, as conclusive evidence that the use of G100UL Avgas is fully compatible with both PSD & PTE sealants when either of those sealants are properly applied during the production of the wings and fuel bays of Cirrus SR22 aircraft.

Conclusion to Full Scale Cirrus Wing PTE Sealant Adhesion Tests 04/19/2024

Conclusion to Full Scale Cirrus Wing PTE Sealant Adhesion Tests 04/19/2024

A) The entire premise underlying Cirrus’ SA24-14 and SA24-14R1 Service Advisory letter(s) is that there is some “inconclusive” aspect to “material compatibility”. However, as demonstrated in PART I, that “material compatibility” premise, for issuing Cirrus SA24-14, is false.

B) Because that premise is false, there is no foundation in fact justifying any statement in the Cirrus Service Advisory, SA24-14, purporting to be in derogation of the safety of the use of G100UL Avgas on Cirrus aircraft and related engines.

C) Cirrus is fully aware of the truth of the matters set forth in paragraphs A) & B) above. Recently, in its private interactions with “industry stakeholders” and others - Cirrus has freely acknowledged that Cirrus has “no technical issue” with the use of G100UL Avgas.

D) In the fifth paragraph of SA24-14R1, Cirrus states:

Per Continental and Lycoming, only approved fuels may be used for an engine to be covered by warranty.

And then Cirrus makes the following false statement:

As the GAMI G100UL fuel is a non-approved fuel per Continental and Lycoming, engines known to have run this fuel may not be covered by the current OEM engine warranty.

(Boldface is in the original published by Cirrus.)

That statement is false. G100UL Avgas is a fuel which the FAA has formally “approved for use” on every Lycoming and Continental Engine. See STC SE01966WI and its associated Approved Model List, dated September 1st, 2022.

E) In SA24-14 & 14R1, Cirrus makes reference to the addition of ASTM D910 Grade 100VLL as having been recently added to its approved fuels, based solely upon the fact that Grade 100VLL has an “ASTM” industry consensus standard specification.

F) The last time we checked the regulations, ASTM does not certify aircraft or engines, nor even approve fuels for use in aircraft or engines.

G) All ASTM does is to define a specification which is for the convenience and use of “purchasing agencies.” The ASTM specification includes no finding that a particular fuel defined in that specification is suitable for a particular airplane nor any particular engine. ONLY the FAA can do that by including or excluding the fuels that are allowed as part of the regulatory “limitations” applicable to each engine and each aircraft.

The first paragraph of ASTM D910-24 (adopted in March of 2024) states the actual purpose and scope of an ASTM fuel specification:

1. Scope

1.1 This specification covers formulating specifications for purchases of aviation gasoline under contract and is intended primarily for use by purchasing agencies.

1.2 This specification defines specific types of aviation gasolines for civil use. It does not include all gasolines satisfactory for reciprocating aviation engines.

Ultimately, paragraph 1.1 of ASTM D910 means that the only purpose of an ASTM fuel specification is to facilitate commerce - primarily between and among the producers, distributors, FBOs, and their customers, the operators of aircraft.

H) Contrast that very limited scope of purpose with the fact that G100UL avgas has both:

1) An FAA approved specification which the FAA has determined is the “equivalent” of (or, in fact, better than) an ASTM consensus standard specification; and,

2) A formal determination by the FAA (which ASTM cannot do) that G100UL Avgas is suitable for use in all spark ignition piston aircraft engines and all of the airplanes that use any of those engines.

From Page 6 of the G100UL Avgas FAA approved specification:

… the FAA has, in fact, made a determination that this Specification and Standard for a High Octane Unleaded Aviation Gasoline provides, not only an equivalent, but, in fact, an enhanced level of quality control of the properties and performance of the aviation gasoline produced under this specification and distributed throughout the supply chain, as compared to the traditional governmental, military, or industry voluntary consensus based standards which have previously defined and controlled the production and distribution of aviation gasolines used for spark ignition piston engines.

Source: FAA G100UL Avgas Specification, Rev -12C9.

I) Strangely, in SA24-14 & 14R1, Cirrus appears to presume to represent and “to speak for” Lycoming and Continental. In that role, Cirrus makes an allegation which presumes that Lycoming and Continental are going to refuse to honor their written OEM warranties if an owner of one of those OEM’s engines elects to use (or is forced by lack of availability of 100LL) to use an alternative, high octane fuel that has been fully approved by the Administrator of the FAA to be used in the operation of every single spark ignition engine in the FAA’s TCDS database, including every one of Lycoming’s and Continental’s engines;

J) Because G100UL Avgas is fully approved by the FAA for use on all Lycoming and Continental Engines, any claim by Lycoming that the use of G100UL Avgas is the use of an “unapproved fuel” which (if true) might violate the Lycoming engine warranty is not a legal position that is likely to prevail in a dispute in which the express language in the Lycoming Warranty will be strictly construed against Lycoming and in favor of the aircraft owner.

See the following legal opinion (dated June 24th, 2024) on this subject found on AVweb, at this location: www.avweb.com/aviation-news/lawyer-pilot-says-g100ul-does-not-void-engine-warranties/

In response to the formal legal opinion published in the AVweb link above, two days later, Lycoming responded and stated:

Lycoming Engines provides a Limited Warranty against defects in material or workmanship. Lycoming’s Limited Warranty does not cover damage caused by operation outside of Lycoming’s published specifications or the use of non-approved fuels or lubricants.

Lycoming appears to be attempting to avoid or evade the fundamental fact that G100UL Avgas is a fuel which the FAA has approved for use in every Lycoming piston engine.

Lycoming may claim otherwise, but as described in the June 24th AVweb legal opinion, Lycoming is bound by the terms of its written warranty with its customers, which makes no allowance for any later, after the fact, “on the fly” exceptions which Lycoming may attempt to create by reference to “service documents”, such as Service Instruction 1070, which is not mentioned or referenced in its written warranty.

https://www.avweb.com/aviation-news/lycoming-clarifies-g100ul-warranty-impact/

Also, again, it is important to note that only a very small fraction of the Lycoming engines in service are still covered by a Lycoming factory warranty.

K) Lycoming may have forgotten the following:

At Oshkosh, in the summer of 2013, GAMI met with the (then) Presidents of both Continental (Rhett Ross) and Lycoming (Michael Kraft). GAMA president Peter Bunce arranged for the meeting. Walter Desrosier of GAMA was in attendance, and the meeting was held in the GAMA trailer/office located on the grounds at Oshkosh.

L) At that time, Mr. Ross and Mr. Kraft conducted a detailed review of the G100UL avgas specification, and related data;

M) Mr. Ross and Mr. Kraft asked a number of informed questions about G100UL avgas and its testing;

N) Background: Both Lycoming and Continental had, in 2010 & 2011 sent company engineers and/or test pilots to GAMI in Ada to conduct test flights using G100UL Avgas. Their report then, was that the use of G100UL Avgas is transparent to the operation of the aircraft operating on 100LL. 1 2

a. At the conclusion of that meeting, and as the last item on the agenda, Mr. Ross and Mr. Kraft were each specifically asked if Continental or Lycoming would object to G100UL avgas being used in their company’s engines;

b. Each of those OEM company Presidents stated then,

If the FAA approves the use of G100UL Avgas on our engines, then my company will not object to the use of that FAA approved unleaded fuel on our engines.

|  |

O) Those statements by Lycoming and Continental’s Presidents have been publicly discussed at Oshkosh and Sun and Fun, periodically since 2013. To date, neither Lycoming nor Continental has taken issue with the veracity of the reporting of those statements.

P) GAMI has, at enormous expense, relied upon those formal representations by the CEO’s of Lycoming and Continental as GAMI spent the next nine years completing the FAA fleet wide approval of G100UL avgas for the entire fleet of Lycoming and Continental spark ignition piston engines;

Q) For those reasons, GAMI would suggest to the management at Cirrus, that any concern they may have about warranty coverage of engines installed in Cirrus aircraft that may arise by their customer’s use of the FAA’s recent approval for the use of G100UL high octane aviation gasoline in their airplanes is contrary to the previous representations of the OEM engine manufacturers’ Presidents and is also contrary to a proper understanding of the correct legal interpretation of the language found in the Lycoming and Continental engine warranties.

R) While Lycoming and Continental may decide to change the wording in their warranties, for engines sold after some date in the future, well settled legal principles state that neither of those companies can unilaterally, and without the consent of the engine owner (who is still under warranty), make a change in the warranty that is retroactive to the purchasers of their engines that are still under warranty.

S) Overriding any of the details of the legal jargon, Lycoming would likely be ill-advised to deny a warranty claim for a starter or a magneto, or an alternator, simply because the owner had used G100UL avgas. Stated another way, in order to evade their legal warranty responsibility, Lycoming would have to establish that the use of G100UL caused the affected component to fail. Given the FAA approved test data available, that outcome would appear to be remote.

Conclusions related to Cirrus, Lycoming, and Continental Warranties

Any warranty issue is completely irrelevant to the vast majority of aircraft owners whose aircraft are outside of the relatively short OEM factory warranty periods.

Even for new Cirrus aircraft warranties, most of the “big ticket” items (other than engines, for which Cirrus is not responsible) are related to the avionics, the propeller, and other systems which are not remotely affected by the history of the owners’ use of leaded or unleaded fuel use in the aircraft.

Answer: Only Cirrus and GAMA and the members of that organization know for sure what the motive of Cirrus might be in issuing SA24-14 & 14R1;

Whatever the real reason may be, clearly it is not, in any way, related to a “safety of flight” issue with the use of G100UL Avgas, nor does it relate to any legitimate concern about warranty coverage;

A number of people have suggested that the real purpose is only to attempt to delay the deployment of G100UL Avgas in order for one of the two remaining PAFI / EAGLE fuels (Swift UL100R and LyondellBasell/VP racing UL100E) to make progress and to thereby be able to identify some tangible accomplishment from the expensive taxpayer-funded EAGLE program;

With respect to the peculiar Cirrus Service Advisory SA24-14 & 14R1, there is no valid reason stated in either SA24-14 or the revised SA24-14R1 to substantiate any claim that the use of G100UL Avgas in any aircraft or engine creates:

ANY ISSUE WITH AIRWORTHINESS; nor

ANY SAFETY OF FLIGHT CONCERN.

GAMI's George Braly gives a presentation on the state of G100UL deployment at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2025. This annotated video includes the presentation and subsequent Q&A section.

G100UL unleaded avgas is the only high octane unleaded avgas approved by the FAA for use in all aircraft piston engines and all piston powered airplanes.

December 20, 2024, G100UL high octane unleaded avgas arrives in Mississippi. Tupelo Regional Airport receives the first shipment.